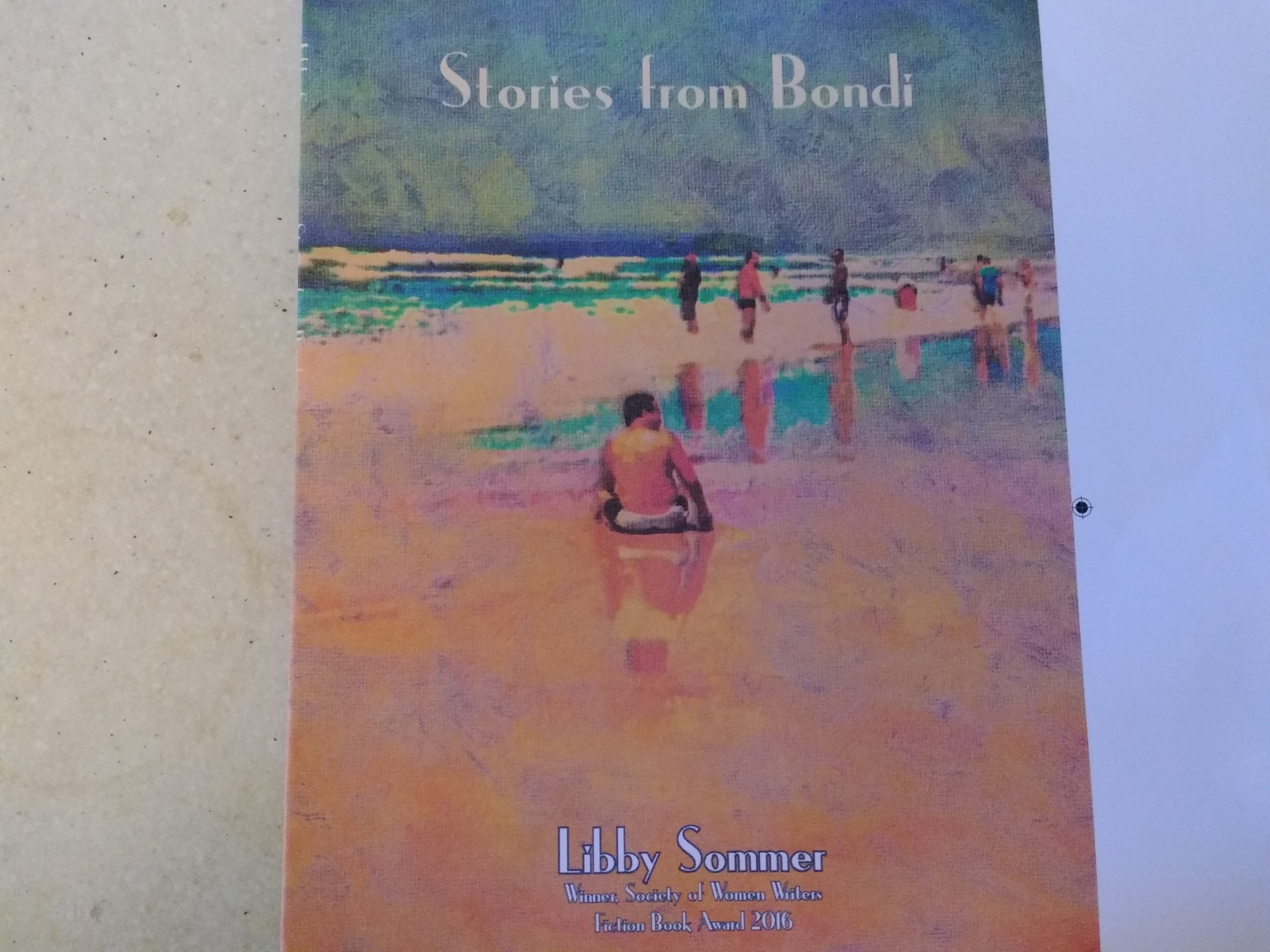

Have a read of my short story, ”Jean-Pierre’, first published in Quadrant Magazine. It’s one of the stories in my collection ‘Stories from Bondi‘ (Ginninderra Press).

I hope you enjoy it.

Jean-Pierre

This was in a far distant land. There were Pilates classes but no surfing beaches or vegan restaurants. People said to hell with low-fat diets and tiny portions. Charles, who had wanted her to hire his friend Jean-Pierre as tour guide, had encouraged her in yoga class. ‘Look, Zina, you’re a facilitator—you’ve been running those groups—for what—thirty years?’

‘Only twenty, for goodness sake.’ She had turned forty-nine and frowned at him upside down between the legs of a downward facing dog. She had a face marked by the sun, a face left to wrinkle and form crevasses by years of smoking, a face made shiny by the application of six drops of jojoba oil, although the shop girl had recommended she use only three. ‘I love that word facilitator. It says so much.’

‘Twenty. All right. This guy’s not at all your type. He’s a numbers man. He shows tourists around in between Engineering contracts. He can show you how to buy a bus or a train ticket, how to withdraw money out of the wall—get your bearings. You can hire him for half a day. Or, in your case, half a day and half the night.’

‘Very funny,’ she said, stifling a laugh. Now they were on all fours arching their backs like cats, then flattening their spines to warm up the discs. Indian chanting music took your mind off the fact that the person behind you was confronted with your broad derriere. ‘So what’s the story with Jean-Pierre?’

‘Someone I met at a conference in Monaco,’ said Charles on an out-breath. ‘Large-yacht communications. He’s charismatic, let me tell you.’ Charles dyed his hair and beard a rich brown, and in yoga class it stood on end to reveal a circle of grey at the crown. He had paid many visits to this far away country since he started learning the language. She’d never had the courage to have a go herself. She knew how to say good morning, Madame every time she walked into a shop, how to ask for the bill, how to say please and thank you. What else did you need? Charles had moved on to German classes and was planning a trip to Berlin with his wife. They were even taking their two kids. Toledo and Paris they called them.

‘Look, you’re going to the land of endless rail strikes,’ Charles said. ‘You’ll need Jean-Pierre, or you’ll be stranded on train platforms, not knowing what to do or where to go.’

‘Come on now. You’re such an exaggerator. They’re not always on strike.’

They lay on their backs, legs wide open in the air in a happy baby pose. ‘All right, I suppose so,’ she said. ‘You can give me his email address.’

‘I love croissants and baguettes and all of that,’ said Charles, sighing over his shoulder.

The yoga instructor was walking around the room, checking out their poses and had reached the back row. ‘Focus inwards, be in the moment,’ he reprimanded Zina and Charles.

‘Let the soles of your feet reach for the ceiling,’ he said before returning to the stage to demonstrate the cosmic egg. He eased his face between his thighs. ‘Now bury your eye sockets into your kneecaps.’

‘I’m not trying to fix you up with JP,’ Charles whispered. ‘I really hate that kind of thing.’ He twinkled across at her.

‘Lift your hips high off the mat and boom your heart toward the back wall.’

Jean-Pierre was still charismatic, and, on close examination, was still handsome. About sixty, with a splendid head of hair. His face was persuasive, his forehead, his large nose. They ate croissants at Cosmo, the busiest café in the village. She drank green tea infused with fresh mint, the leaves determined to block the spout of the tea pot. Jean-Pierre sipped on an espresso.

He nodded at her tea. ‘English,’ he said with a note of barely disguised distain. ‘The English drink tea.’

She bristled. A racist. A narrow-minded, insular, arrogant racist.

She looked at his intense face as he stroked the black and white head of his dog who peeped out above the zip of his jacket and felt sorry for his preconceptions and a little sorry for herself when she reflected on it, because, really, he seemed to know very little about Australia. Do you have black Africans living off social security? Poor Jean-Pierre didn’t know an African from an Aborigine.

‘No, green tea is not English,’ she said haughtily, giving him the evil-eye, to show him, to show him this: ‘Green tea originated in China.’

Madame?’ said the waiter, reaching for her empty plate.

‘Merci,’ she nodded.

‘Did you fly Business?’ Jean-Pierre said abruptly. ‘Such a long flight from Australia.’

‘Economy. I’m a poor struggling facilitator.’

‘You have to get out there and promote your courses. Then you can fly Business.’

‘We don’t all do things just for the money.’

Jean-Pierre looked down the narrow cobbled pedestrian-only street. ‘There are two things you must watch out for here,’ he said. ‘The motor bikes … and the dog pooh.’

‘Thanks,’ she said, then, trying to be friendly. ‘In New York they say you can tell the tourists from the locals because the tourists are the ones looking up at the skyscrapers and the locals are the ones looking down for the dog pooh.’

He twisted the gold band that girded the blowsy fat of his finger. ‘I was married to a New York lawyer once. Very clever. She read four books a week. I read only one a month. Are you married?’

‘Not currently.’

‘My son speaks four languages,’ said Jean-Pierre. ‘My mother likes to say that anyone can get a Masters, but if you’ve got four languages—rather than three—you’ll be a success in life. I’ve only got three. What about you? Any children?’

Eli had stayed at her place for the week just before she left home. He’d sat in the lounge room, eyes fixed to his iPad. She would sometimes watch on as he played a combat game. He’d build a village, train his troops and take them into battle. She would watch his face deep in concentration, so focused he seemed unable to hear when she asked him to set the table, or unstack the dishwasher. She didn’t like the every-second-week-deal with his father, so disruptive to getting a routine in place. Eli would come with her to the gym sometimes, or they’d go for a jog around the oval. It’s not as if his father did any of those things. She did her best: drove Eli to cricket and footie, helped with his homework, listened whenever he was willing to talk, always made sure there was meat in the house when it was her week “on”. Eli said to her, ‘When you and Dad were together, we always ate with the TV turned off. Now you’re divorced, you and me can eat dinner in front of the tele if we feel like it. Much better.’

‘Yes,’ she said to Jean-Pierre. ‘I have a son.’

‘It’s different in this country. We’re Catholics. We don’t usually divorce. Not when there are children. Are you a Catholic?’

‘No.’

‘Religious?’

‘Spiritual, but not religious. We could do with less religion in the world, in my opinion. Why?’

‘I was going to suggest I show you the island of Saint Honorat off Antibes, but tourists only go there in order to see the sacred abbey. The thing is, I grew up in Antibes. I know it like the back of my hand. I could hire a car and we can drive to different parts that the tourists don’t see. We can spend a few hours in Antibes, then, after that, if you want, we can have lunch. What do you think?’

‘What would it cost?’

‘Well, there’s the cost of the car, then my time. So … all up, 180 euros.

‘I’ll give it some thought.’

Jean-Pierre lowered his dog to the ground, reached for his wallet, pulled out a ten euro note and placed it on the edge of the table for the waiter.

She unzipped her handbag to pay her share but he patted her on the arm and said proudly, ‘No. No. Put your money away. I’m a Frenchman.’

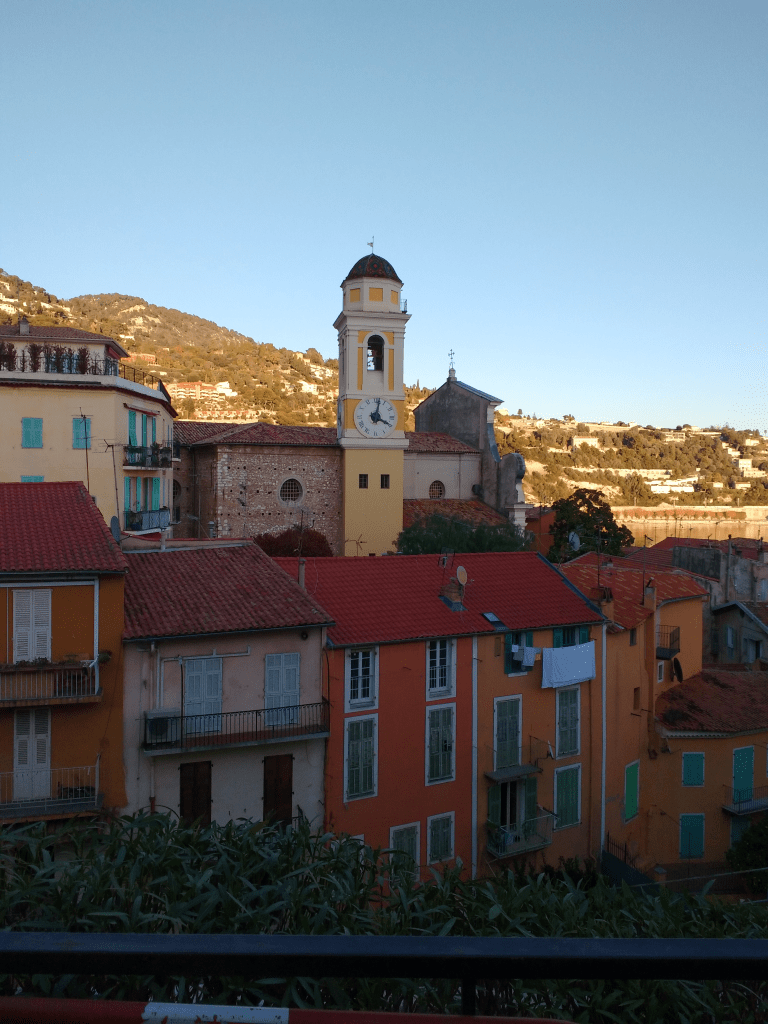

The second time they met up, they went for a walk into Nice via the foreshore. It was a difficult walk. Eighty sets of steps interspersed with slippery limestone rocks. When she asked why the gate was locked at the end of the walk, necessitating a dangerous climb over a high fence on the edge of a cliff, Jean-Pierre said the authorities probably kept the gate locked because they didn’t want tourists getting washed off the rocks at high tide. It wasn’t a good look.

Now he wanted to have lunch at the Port.

‘Where do you like to eat?’ she asked. She was still thinking about the climb over the gate, when she’d been so afraid that she wouldn’t be able to get her leg high enough and would crash to an early death on the rocks below. She’d needed to sit on the stone wall to compose herself afterwards. It was Jean-Pierre who had acknowledged her courage, had said she’d done well, that she’d even looked graceful when she’d executed the tricky maneuver and swung herself out into the void before throwing herself over the top. Before they’d left on the walk he’d told her he hadn’t followed the coastline into Nice for a long time, and was really looking forward to walking it again. He wouldn’t be charging her his usual hourly rate, as it was something he’d been wanting to do for ages. ‘My wife kept me on a tight leash.’

‘There are plenty of places to eat at the Port,’ he said. They walked down the hill and he leaned in and gave her shoulder a quick squeeze. ‘You did well,’ he repeated. She blushed with embarrassment at the intimacy of his gesture. She’d only just met him, after all. And anyway, she was no good at relationships. There were people she knew who were good at them and people who weren’t. She was no good.

‘What sort of restaurant do you like to lunch at back home?’ he said.

‘We mostly don’t have a big meal in the middle of the day.’

‘No? What do you do?’

‘Well, um, we usually jog around the park, then stand in line to order large skimmed lattes.’

‘Ah,’ he said, and put his hand over hers where it rested on the table. She felt her hand go still like a frightened animal. Jean-Pierre’s hand was rough and warm as it lay over hers. Maybe she shouldn’t have drunk two beers in the middle of the day.

On Saturday afternoon Jean-Pierre took her and a group of American tourists by ferry to an old island prison. ‘You’ll find this place worth a visit,’ he said, as they waited on the wharf. ‘An infamous jail for deportees, prisoners convicted of political crimes, such as espionage or conspiracy.’

‘Interesting,’ she said, stepping across the gangplank. She sat down beside Jean-Pierre at the front of the boat. The four American couples filed down to the back row of seats. ‘We can throw Smarties at you from here,’ one of them joked.

Jean-Pierre tapped on her sunshade. ‘You won’t need this. It’s dark in the cells.’ He pulled a map out of his pocket and opened it out, pointing to the layout of the buildings. ‘The locations of the public toilets,’ he said. ‘That’s what every tour guide needs to know.’ He folded up his map and put it in his breast-pocket. ‘I want to give you a quick kiss now, before we get into one of those dark cells,’ he said. ‘I won’t be able to see you in there.’ He turned towards her, and suddenly his face, up very close, appeared at the end of her nose, floating, as she leant against the back of the seat. He shut his eyes and kissed her, soft and probing, and she kept her sunshade on for privacy, lips, mouth, teeth and tongue, his hand moving very slowly up her arm, up to her shoulder and to her bare neck, and hovered there for only a moment, cradling her face, before he moved away, straightened his trousers, and quietly pulled out his map again.

She adjusted herself and stared out the window to the water. Jean-Pierre gave the signal that they were nearing their destination and to prepare for disembarkation.

‘We don’t do things like that in Sydney,’ murmured Zina. She refreshed her lipstick.

‘No?’ Jean-Pierre grinned and levelled out her visor.

‘No, it’s um, all those coffees. You just keep running. Forever and ever. You spend your whole life,’ her hands juggled an imaginary Tai Chi ball—‘on the run.’

Well-kept concrete walkways led up, over and around the island’s hill. Jean-Pierre steered them through a rustic entrance to the old prison complex.

‘And now,’ he said, ‘we come to that part of our tour most likely to give you claustrophobia. The Reclusion Disciplinaire area.’

They stepped up and through a narrow hallway toward the low, dark solitary confinement cells.

‘This is where prisoners were kept in silence and darkness,’ Jean-Pierre was saying. He led the way into the dark of the single-person cells. ‘You won’t be able to see a thing in there.’

She squinted ahead at the front of the group, which had now gathered by the doorway. It looked scary. She took off her sunglasses and shade, but could see nothing as she stepped in. The blackness lay heavily all around, not like a moonless sky, but like a creepy cupboard with stone walls and low roof, a stone tomb. There was something inhuman in the cruelty of the space, a place where the light never shone, hidden, despair-inducing.

‘I’m right behind you,’ Jean-Pierre said, moving close, ‘in case you’re frightened.’ He gave her hand a squeeze, then placed his arm around her waist. She could smell his after-shave—or was it cologne?—feel the warmth of his breath on her neck, and leaned, unseeing and anxious, into his body. She reached for his arm and clutched at his hand where it rested on her waist.

***

When they went to bed together, she almost broke into joyous laughter. He’d drawn her in without even trying. His face, his voice, his eyes. It was a whole-package thing. He made her feel so special. He was more appreciative than anyone she had ever known. He hugged and kissed and even offered to go downstairs and get her cigarettes out of her handbag.

He got out of bed and went over to the piano. He fumbled with some sheet music in the semi-dark, holding each up to the light until he found what he wanted.

‘I play this sometimes,’ he said, in a quiet voice. ‘It starts with a single note, a B natural, growing in dynamic from a soft pianissimo to a very loud fortissimo.’ She listened as he played the one note, building up to full strength. Who was this guy?

When he’d finished, he turned to her and said, ‘Especially for you. I use my music to express my feelings.’

They made love again. Once more he got out of bed and sat beneath the black and white photograph of himself with his mother and his brother. He began to play. After a while he stopped playing and went into the bathroom to wash his hands. When he returned he wore the hand towel looped over his erect penis. She rolled over to have a look and kissed him, his face glowing with pride.

Morning. The bakeries were laying out their breads and pastries filling the air with the mouth-watering aroma of freshly baked baguettes. In the antique shop windows, as the sun struck them, the cleaners hosed the cobbled alleys. Jean-Pierre rose early and walked to the boulangerie.

He laid the breakfast out on a tray and brought it in to her in bed. Outside the window, the sky was a clear faded blue, and patches of sun, geometric designs of light, streaked the doona. He put the tray on the bed, and she sat up and stroked his face, his skin still chilled from the morning air. She pointed at the pain au chocolat.

‘So I need to forget about the diet?’

‘Oui.’ His mouth was already filled with pastry, chocolate oozing between his lips. ‘It’s good for you. Don’t you know that the flour in this country is so good, and so different, that even gluten-intolerant people can eat the bread and quiches?’

Her workshops, as she wrote to Eli back home, were going well. She’d managed to book a space in an old 16th century Citadel overlooking the Mediterranean. And she’d made a new friend. Something had happened to her in an old isolation cell, she didn’t know what exactly. But she had to get back home. I hope you and Dad are getting on okay and he hasn’t had any more nasty blow-ups. It’s a mild winter here. Some people are even swimming and sunbaking on the beach. Love, Mum

They went on the bus to visit his mother, the music of Bach on a score above his head. In Bach there was not only symmetry and logic but more, a system, a reiteration which everything hinged on. His hair was uncombed. His face had the modesty, the unpretentious lips of someone secretly able to calculate the frequencies of the string vibrations. His mother met him at the door and took his dark face in her hands. She stepped back to see better.

‘Your hair,’ she said.

He combed it down with his fingers. His brother came from the kitchen to embrace him.

‘Where have you been?’ he cried.

At night Jean-Pierre began to sleep with one hand resting on her solar plexus, the other curled around her shoulder, as if to shield her from bad dreams.

When she slept against him like that, her life on the other side of the world crumpled into her backpack that hung on a hook behind the door. Could she live the rest of her life in a far-away-country? Maybe she could. Except for that funny feeling in the pit of her. Like a rock in the guts.

On Sunday morning Jean-Pierre took her for a walk up to Mont Baron. ‘You’ll love the view from the old Fort,’ he said. ‘You can see Italy to the left and Nice to the right.’

‘Sounds wonderful!’ she said, closing the door behind them. They climbed the steep steps that led up the hill. The sky was gold with light.

‘Why don’t you come with me to Australia?’ she said.

‘I don’t think so.’

She listened to the sound of water over rocks.

‘No?’ she said.

He was silent. After a moment he said, ‘I can’t.’

She began to imagine she could hear the sound of a kookaburra laughing.

‘No,’ she said. ‘I think I should stay here with you.’ She reached for his hand.

‘No, you can’t. I can see you phoning Eli to tell him you’d decided to stay and him crying, No, Mummy. Come home.’

‘You know us Australians,’ she said, suddenly desperate. ‘We’re like boomerangs. We keep on coming back.’

She went into the bedroom to change her clothes. He started to follow her but sat down again instead. He could hear intermittent, familiar sounds, drawers opening and being shut, stretches of silence. It was as if she were packing.

‘Are you really leaving on Saturday?’ he said.

‘What did you say?’

‘Saturday. Is that it then?’

‘Why don’t you come with me?’

‘I could never live in a country with no European history. But I’ll surprise you one day. I’ll ring Eli early and ask what beach you’re walking on and I’ll just turn up on the sand.’

During that last day she thought of nothing but Jean-Pierre as she packed and cleaned out her little apartment.

‘What do you do, you have a stopover in Dubai?’ Jean-Pierre said, standing next to her at the taxi rank in the early morning chill. A bitter wind blew from the mountains. He had come over to carry her bag down the stairs.

‘I go straight through. It’s three hours on the ground in Dubai, so I walk around the airport then read my book.’

Jean-Pierre looked directly into her eyes. ‘I’ve bought you a little gift,’ he said.

‘You have?’

‘Don’t unwrap it until you’re on the plane.’

She smiled. ‘Okay.” Then she looked at his face, to place him clearly in her mind. He was wearing a white t-shirt and blue jeans under a padded coat. She kissed him on the lips, then got into the taxi.

‘Something to take with you,’ he said, leaning in the window. In his hand he clasped a small gift-wrapped box. The sun, still low on the horizon, cast an amber glow on his precious face.

‘Thank you,’ she said. She reached for his hand through the window and then put on her seatbelt.

And she thought about this all twenty-four hours of the journey across the Indian Ocean. She would keep opening the little box to admire the marquisite earrings he’d given her. She would catch a taxi from the airport and at home notice the house smelt musty; she would open all the doors and windows to let the air move through, the curtains blowing and air coming in and out. From a far-away-place, and at night, he would ring to say, resignedly, ‘My mother is living with me now.’ His gift, when she’d take the earrings out of their black box, would remind her of something that had happened to her once.

She felt like someone who she had always known, that old friend of herself, grounded in home, decisions already made, and behind her somewhere, like the shadow of an identical twin, her other self, who must remain in the far-off distance, never to be exposed to the light.

Copyright © 2023 Libby Sommer