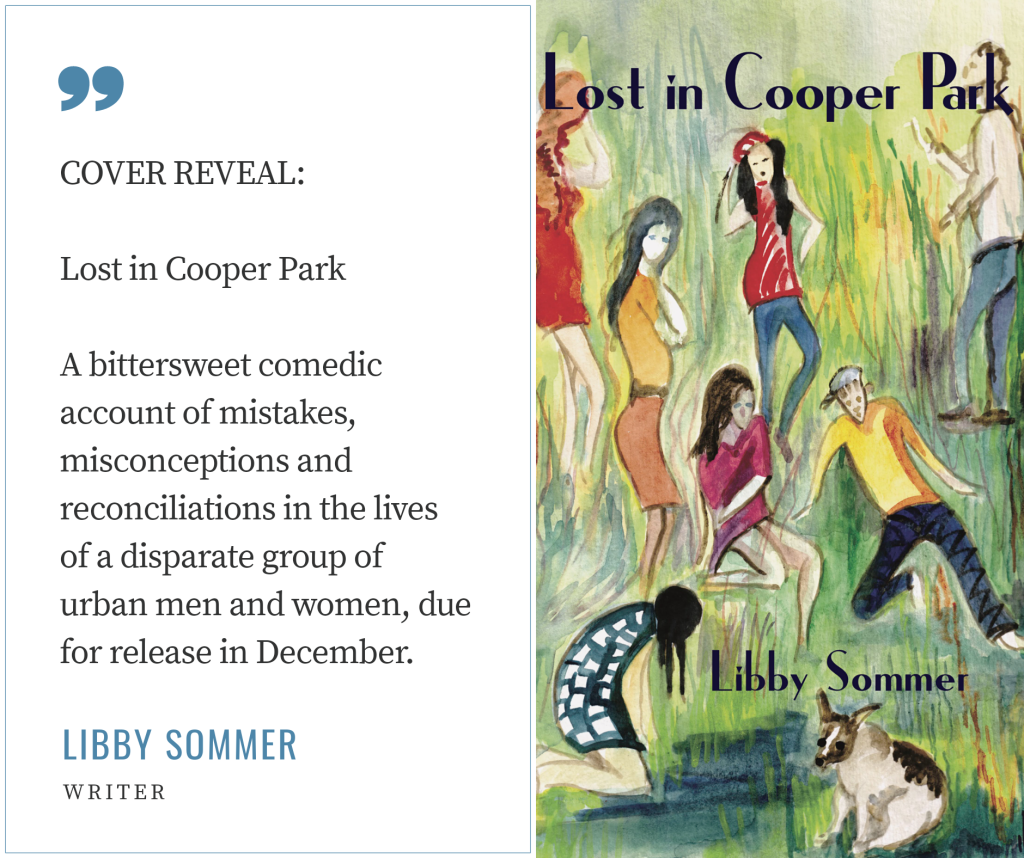

What do you think? Do you like the cover? My new book is due for release by Ginninderra Press next month.

What do you think? Do you like the cover? My new book is due for release by Ginninderra Press next month.

I’ve been slaving away trying to write a good blurb for my soon to be released by Ginninderra Press new book, ‘Lost in Cooper Park’.

Writing a blurb is hard hard work. There are no shortcuts or easy answers. Anyway, after a chat with a close writing friend, this is what I’ve put together for the back cover.

The story begins when, after a fierce storm, Gypsy, a golden Labrador, goes missing in Sydney’s Cooper Park.

A bittersweet comedic account of mistakes, misconceptions and reconciliations in the lives of a disparate group of urban men and women.

There’s Crystal, who wants stability with her eight-year-old daughter and new partner.

Crystal’s ex, searching for the meaning of existence.

Doctor Sarah wanting a new beginning in France.

Rosemary and Philip who want their daughter to walk again.

Crystal’s high school sweetheart who wants another chance.

And the Homeless Girl hiding in Cooper parklands.

And then there’s the cruelty, unpredictability and beauty of life.

Back cover blurb: ‘Lost in Cooper Park’ by Libby Sommer

Tell me what you think? Would you be interested in reading this book?

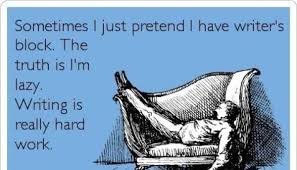

Have a read of my flash fiction ‘Sober Sixty’ first published in the August 2020 Grieve Anthology, Stories and Poems of Grief and Loss.

Sober Sixty:

Samantha’s single women friends were envious, although she assured them Johnny wasn’t perfect. Mood swings, challenging stuff like that.

Nobody messed with Johnny. Nobody knew better than he did, he was always watching YouTube and learning new facts and figures. Also, he rode a motorbike and practiced shooting at weekends. There were Facebook groups for bike riders and a rifle range nearby. Johnny was proud of being a rev-head and a good shot with his gun, and not many people could disagree that he had unusual interests for a man his age.

‘Sober since forty and counting,’ he said about his sobriety. They didn’t talk about his twenties and thirties.

There’s a photograph of the two of them from Christmas day. Johnny had tried to lower himself to Samantha’s height for the photo so they’d be on the same level. ‘Stand up tall,’ she’d said. ‘Stand to your full height.’ ‘That’s right,’ he’d said. ‘You like things big.’

‘What does ATP in ATP Cup stand for?’ was the type of thing Johnny would call out while she poured him a glass of water before setting out on a stroll around the block.

Samantha thought she knew the answer, but didn’t want to risk being wrong. She’d learnt to tiptoe around his wildness and dreaded the fighting when she wasn’t attentive enough to his needs. Dry drunk, AA called it. The unpredictable rages were doing her head in. She knew she needed the courage to walk away.

Now she’s getting by a day at a time.

Her friends say she’s one of the lucky ones. She’s dodged a bullet.

Copyright © Libby Sommer 2020

Grieve 2020 Anthology available from Hunter Writer’s Centre website or Booktopia https://hunterwriterscentre.org/bookshop/

I highly recommend ‘Becoming A Writer’ by Dorothea Brande given to me by a friend many years ago at the beginning of my writing journey.

‘A reissue of a classic work published in 1934 on writing and the creative process, Becoming a Writer recaptures the excitement of Dorothea Brande’s creative writing classroom of the 1920s. Decades before brain research “discovered” the role of the right and left brain in all human endeavor, Dorothea Brande was teaching students how to see again, how to hold their minds still, how to call forth the inner writer.’ – Amazon

‘Refreshingly slim, beautifully written and deliciously elegant, Dorothea Brande’s Becoming a Writer remains evergreen decades after it was first written. Brande believed passionately that although people have varying amounts of talent, anyone can write. It’s just a question of finding the “writer’s magic”–a degree of which is in us all. She also insists that writing can be both taught and learned. So she is enraged by the pessimistic authors of so many writing books who rejoice in trying to put off the aspiring writer by constantly stressing how difficult it all is.

‘With close reference to the great writers of her day–Wolfe, Forster, Wharton and so on–Brande gives practical but inspirational advice about finding the right time of day to write and being very self disciplined about it–“You have decided to write at four o’clock, and at four o’clock you must write.” She’s strong on confidence building and there’s a lot about cheating your unconscious which will constantly try to stop you writing by coming up with excuses. Then there are exercises to help you get into the right frame of mind and to build up writing stamina. She also shows how to harness the unconscious, how to fall into the “artistic coma,” then how to re-emerge and be your own critic.

‘This is Dorothea Brande’s legacy to all those who have ever wanted to express their ideas in written form. A sound, practical, inspirational and charming approach to writing, it fulfills on finding “the writer’s magic.”‘ – John Gardner

Do you have a favourite book about the writing process that you’ve found to be especially useful on your writing journey?

This declarative sentence was spoken by Don Corleone (played by Marlon Brando) in the movie The Godfather (1972).

We don’t always make declarative statements. It is not uncommon for women and other minority groups to add qualifiers to their statements. Such as ‘Parents need to stop organising every minute of their children’s spare time, don’t you think?’ ‘I loved that movie, didn’t you?’ In our sentence structure we look for reinforcement for our thoughts and opinions. We don’t always make declarative statements such as: ‘This is wonderful.’ ‘This is a catastrophe.’ We look for re-enforcement from others.

Another thing we do without realising it, is use indefinite modifiers in our speech: perhaps, maybe, somehow. ‘Maybe I’ll take a trip somewhere.’ As if the speaker has no power to make a decision. ‘Perhaps it will change.’ Again, not a clear declarative sentence like, ‘Yes, nothing stays the same.’

It is important for us as writers to express ourselves in clear assertive sentences. ‘This is excellent.’ ‘It was a red dress.’ Not ‘The thing is, I know it sounds a bit vague, but I think maybe it was a red dress.’ Speaking in declarative sentences is a good rehearsal for trusting your own ideas, in standing up for yourself, for speaking out your truth.

When I write poetry I read through early drafts with a critical eye, taking out indefinite words and modifiers. I attempt to distill each moment to its essence by peeling off the layers until the heart of the poem is exposed. We need to take risks as writers and go deep within ourselves to find our unique voices and express ourselves with clarity.

Even if you are not 100% sure about your own opinions and thoughts write as if you are sure. Dig deep. Be clear. Don’t be vague on the page. If you keep practicing this, you will eventually reveal your own deep knowing.

What about you? Have you noticed this tendency to qualify in your conversations with others, or in your creative writing, or in your blog posts?

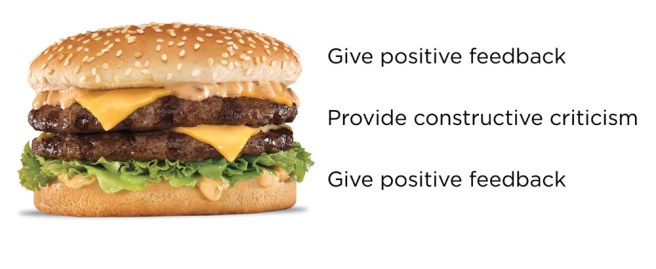

In the Saturday feedback group, we began talking about the ‘off with his head’ or ‘out-it-goes’ part of writing. We acknowledged that as a group we’d always been very supportive and encouraging of each others work. That was because we were all in it together. Our critiquing was not telling lies; it was from a place of open-hearted acceptance. Everything you put on the page is acceptable.

Sometimes someone says, ‘I want a rigorous no-holds-barred assessment of my work.’ But what do you say to them when the writing is dull and boring? Don’t give up your day job? It doesn’t sit comfortably with most of us to be directly critical of someone’s writing. It’s like telling someone how ugly their baby is. All of us find it hard to separate our writing from ourselves, and are prone to take criticism personally.

The feedback sandwich is a widely known technique for giving constructive feedback, by ‘sandwiching’ the criticism between two pieces of praise or compliments.

Yesterday, as we passed around copies of our work (just a page or two) we started to address what William Faulkner famously said:

‘In writing, you must kill all your darlings.’

First of all, we looked for the juice in each piece. Where did the writing come alive? ‘Get rid of the rest,’ we said. ‘Off with his head—out it goes.’ It’s very difficult to be this honest, and not everyone wants to hear it. ‘I simply want gentle support and a few corrections,’ some of us might say.

Be willing to have the courage to look at your work with truthfulness. It’s good to know where your writing has energy and vitality, rather than to spend a lot of time trying to make something come to life that is dead on the page. Keep writing. Something new will come up. You don’t want to put your readers to sleep by writing a lot of boring stuff.

Do you have a writing group? Do you find it useful?

David Dale in the Sydney Morning Herald writes about Isaac Newton’s self-isolation during the plague year 1665-66 and how he passed the time.

‘Newton was 23, a student at Cambridge. When the black plague spread there from London, he retreated to his birthplace – Woolsthorpe Manor, near the town of Grantham (later the birthplace of Margaret Thatcher). During what he called his “annus mirabilis”, or wonderful year, at Woolsthorpe, Newton did three significant things:

He invented the mathematical system called calculus,

He drilled a hole in the shutter of his bedroom window and held a prism up to the beam of sunlight that came through it, discovering that white light is made up of every colour (and giving Pink Floyd an iconic album cover), and

He watched apples falling from the trees in his garden and theorised about a force called gravity, which keeps the moon revolving around planet Earth. (He later wrote: “I can calculate the movement of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”)’ – Sydney Morning Herald

So what can you do while in isolation amid the corona virus outbreak to stay calm and centred and to concentrate your mind away from the current crisis? A writing project could be the answer.

What to write? If you’ve been wondering whether to write a short story or a novel, here are some thoughts on these two different forms of creative fiction:

Is a novel a short story that keeps going, or, is it a string of stories with connective tissue and padding, or, is it something else? Essayist Greg Hollingshead believes that the primary difference between the short story and the novel is not length but the larger, more conceptual weight of meaning that the longer narrative must carry on its back from page to page, scene to scene.

“It’s not baggy wordage that causes the diffusiveness of the novel. It’s this long-distance haul of meaning.” Greg Hollingshead

There is a widespread conviction among fiction writers that sooner or later one moves on from the short story to the novel. When John Cheever described himself as the world’s oldest living short story writer, everyone knew what he meant.

Greg Hollingshead says that every once in a while, to the salvation of literary fiction, there appears a mature writer of short stories—someone like Chekhov, or Munro—whose handling of the form at its best is so undulled, so poised, so capacious, so intelligent, that the short in short story is once again revealed as the silly adjective it is, for suddenly here are simply stories, spiritual histories, narratives amazingly porous yet concentrated and undiffused.

When you decide you want to write in a particular form—a novel, short story, poem—read a lot of writing in that form. Notice the rhythm of the form. How does it begin? What makes it complete? When you read a lot in a particular form, it becomes imprinted inside you, so when you sit at your desk to write, you produce that same structure. In reading novels your whole being absorbs the pace of the sentences, the setting of scenes, knowing the colour of the bedspread and how the writer gets her character to move down the hallway to the front door.

I sit at my desk thinking about form as a low-slung blanket of cloud blocks my view of the sky. Through the fly screen I inhale the sweet smell of earth after rain as another day of possibility beckons.

Self-isolation can give us an opportunity to create something new.

Good luck everyone during this horrific pandemic and please take care.

When people ask me where I get my ideas from, I tell them I use the world around me. Life is so abundant, if you can write down the actual details of the way things were and are, you hardly need anything else. Even if you relocate the French doors, fast-spinning overhead fan, small red Dell laptop, and low kneeling-chair from your office that you work in in Sydney into an Artist’s Atelier in the south of France at another time, the story will have truth and groundedness.

In Hermione Hoby’s interview with Elizabeth Strout in the Guardian newspaper, the Pulitzer prize winner said her stories have always begun with a person, and her eyes and ears are forever open to these small but striking human moments, squirreling them away for future use. “Character, I’m just interested in character,” she said.

“You know, there’s always autobiography in all fiction,” Strout said, referring to her novel, My Name is Lucy Barton. “There are pieces of me in every single character, whether it’s a man or a woman, because that’s my starting point, I’m the only person I know.” She went on to explain:

“You can’t write fiction and be careful. You just can’t. I’ve seen it with my students over the years, and I think actually the biggest challenge a writer has is to not be careful. So many times students would say, ‘Well, I can’t write that, my boyfriend would break up with me.’ And I’d think, you have to do something that’s going to say something, and if you’re careful it’s just not going to work.”

At the launch of one of my books MC Susanne Gervay OAM said: “Libby’s level of detail creates poignant insights into character and relationships. If people know Libby they may find themselves subtly entwined in one of her stories.”

On Goodreads’ website they locate The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath under “Autobiographical Fiction” and describe the book as Plath’s shocking, realistic, and intensely emotional novel about a woman falling into the grip of insanity:

“Esther Greenwood is brilliant, beautiful, enormously talented, and successful, but slowly going under—maybe for the last time. In her acclaimed and enduring masterwork, Sylvia Plath brilliantly draws the reader into Esther’s breakdown with such intensity that her insanity becomes palpably real, even rational—as accessible an experience as going to the movies. A deep penetration into the darkest and most harrowing corners of the human psyche, The Bell Jar is an extraordinary accomplishment and a haunting American classic.”

My advice to you, dear writer, is to be awake to the details around you, but don’t be self-conscious. “So here it is. I’m at a Valentine’s Day party. It’s 33 degrees outside. The hostess is sweltering over a hot oven in the kitchen. She is serving up cheese and spinach triangles as aperitifs.” Relax, enjoy the party, be present with your eyes and ears open. You will naturally take it all in, and later, sitting at your desk, you will be able to remember just how it was to be eating outside in the heat under a canvas umbrella, attempting to make conversation with the people on either side of you, and thinking how you can best make an early exit 🙂

In the interview with Elizabeth Strout in the Guardian, Strout said:

“I don’t want to write melodrama; I’m not interested in good and bad, I’m interested in all those little ripples that we all live with. And I think that if one gets a truthful emotion down, or a truthful something down, it is timeless.”

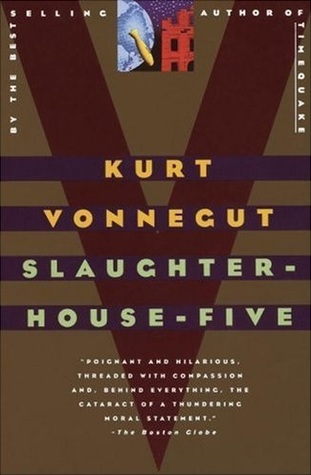

A fantastic example of this writing advice is Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five.

Poignant and hilarious, threaded with compassion and, behind everything, the cataract of a thundering moral statement. – The Boston Globe

Kurt Vonnegut’s absurdist classic Slaughterhouse-Five introduces us to Billy Pilgrim, a man who becomes unstuck in time after he is abducted by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore. In a plot-scrambling display of virtuosity, we follow Pilgrim simultaneously through all phases of his life, concentrating on his (and Vonnegut’s) shattering experience as an American prisoner of war who witnesses the firebombing of Dresden.

Don’t let the ease of reading fool you – Vonnegut’s isn’t a conventional, or simple, novel. He writes, “There are almost no characters in this story, and almost no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick, and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces. One of the main effects of war, after all, is that people are discouraged from being characters.”

Slaughterhouse-Five is not only Vonnegut’s most powerful book, it is also as important as any written since 1945. Like Catch- 22, it fashions the author’s experiences in the Second World War into an eloquent and deeply funny plea against butchery in the service of authority. Slaughterhouse-Five boasts the same imagination, humanity, and gleeful appreciation of the absurd found in Vonnegut’s other works, but the book’s basis in rock-hard, tragic fact gives it a unique poignancy – and humor. – Goodreads

Highly recommended. A masterpiece.

I’m delighted to tell you that my fifth manuscript, LOST IN COOPER PARK has been accepted for publication by small but prestigious publisher Ginninderra Press. Ginninderra is an award-winning independent publisher based in Port Adelaide, South Australia. They publish thought-provoking books for inquiring readers.

Thank g-d for Ginninderra. If it weren’t for them, my books wouldn’t be out there in the world.

LOST IN COOPER PARK is set in Cooper Park, a unique, large, natural green space in the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney with hidden trail walks, tennis courts, picnic areas and dog walking. A great location for a writer like me to come up with a story idea. The book is a continuous narrative this time, rather than a collection of linked stories.

Ginninderra Press’s unique philosophy is:

We believe that all people – not just a privileged few – have a right to participate actively in cultural creation rather than just being passive consumers of mass media. Our culture is revitalised and enriched when everyone is encouraged to fulfil their creative potential and diminished when that creative potential is stifled or thwarted. We love to observe the transformative possibilities for people when they see their work published and acknowledged. Getting published can and does change lives.

Information about Ginninderra on the website includes:

‘Ginninderra is part of Canberra’s Belconnen area, in which Ginninderra Press operated for its first twelve years before moving to Port Adelaide in 2008. Ginninderra is an Aboriginal word said to mean ‘throwing out little rays of light’.

‘Ginninderra Press, described in The Canberra Times as ‘versatile and visionary’, is an independent book publisher set up in 1996 to provide opportunities for new and emerging authors as well as for authors writing in unfashionable genres or on non-mainstream subjects. In the words of one of our authors, we are ‘a small but significant publisher of small but significant books’. Many of our titles have won awards (to see a full list, click here).

‘Ginninderra Press recognises the fact that many people have good ideas for books but cannot get them published, either because of their inexperience in preparing manuscripts or because the potential sales are insufficient to interest a conventional publisher. Ginninderra Press offers expert editing and proofreading, as well as design and lay out services. To see submission guidelines, click here.’

Thank you, thank you, thank you to Ginninderra Press. LOST IN COOPER PARK is due for publication in November 2020. So exciting!