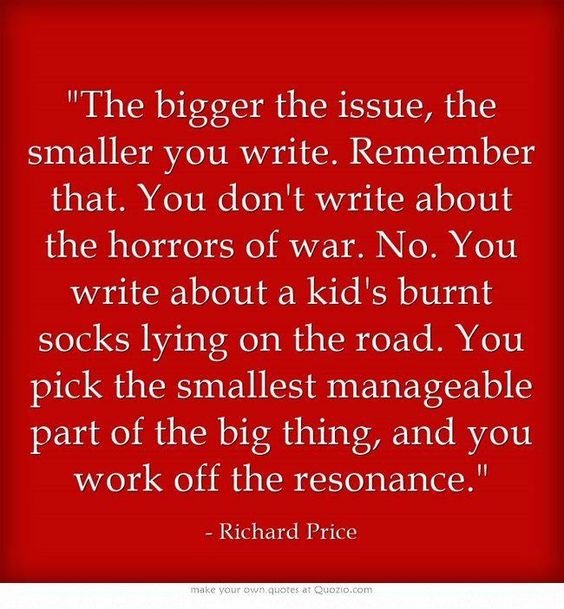

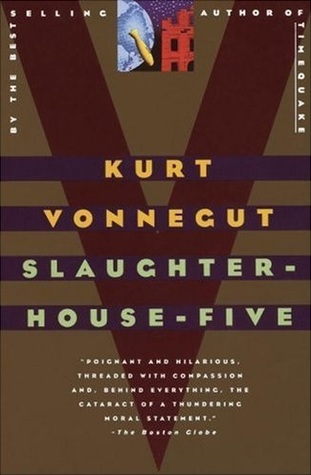

A fantastic example of this writing advice is Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five.

Poignant and hilarious, threaded with compassion and, behind everything, the cataract of a thundering moral statement. – The Boston Globe

Kurt Vonnegut’s absurdist classic Slaughterhouse-Five introduces us to Billy Pilgrim, a man who becomes unstuck in time after he is abducted by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore. In a plot-scrambling display of virtuosity, we follow Pilgrim simultaneously through all phases of his life, concentrating on his (and Vonnegut’s) shattering experience as an American prisoner of war who witnesses the firebombing of Dresden.

Don’t let the ease of reading fool you – Vonnegut’s isn’t a conventional, or simple, novel. He writes, “There are almost no characters in this story, and almost no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick, and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces. One of the main effects of war, after all, is that people are discouraged from being characters.”

Slaughterhouse-Five is not only Vonnegut’s most powerful book, it is also as important as any written since 1945. Like Catch- 22, it fashions the author’s experiences in the Second World War into an eloquent and deeply funny plea against butchery in the service of authority. Slaughterhouse-Five boasts the same imagination, humanity, and gleeful appreciation of the absurd found in Vonnegut’s other works, but the book’s basis in rock-hard, tragic fact gives it a unique poignancy – and humor. – Goodreads

Highly recommended. A masterpiece.