Interviewer: I would like you to tell me about your Path to Publication from first idea to finished book. I’d like to know your inspirations and how The Crystal Ballroom became more than an idea. I also want to know about your writing process. Do you sit at a desk 9-5 or at a cafe during snatched lunches? Did you write the book in a spurt of three months … how long did it take from start to finish? Did you have cold readers, send it to an agent or to a publisher? Were you accepted straight away? How many rewrites and drafts?

Me: I usually write stories about places and people that I know well. I take real events and characters but change things around and shake them all about and make things up. So, for The Crystal Ballroom, I had been dancing Argentine tango, rock and roll, jive, swing, Latin American and ballroom dancing for many many years. I used to dance five nights a week. I’d drive all over Sydney for technique classes and to dance at different venues. The place, ‘The Crystal Ballroom’, is a fiction but this dance hall becomes a character in the novel. I was inspired by the people I met at the dances and the politics of the ‘dance scene’.

I don’t sit at a desk 9-5 but I am extremely disciplined with my writing. I write 7 days a week. I treat my manuscript like an old friend, someone I need to stay in touch with regularly. I also exercise 7 days a week. So my routine is to go to a cafe before the gym with a print out of the previous day’s work. I edit from this hard copy and write the next scene. After the gym I walk home, type out the revisions, print out, go to another cafe in the afternoon. Repeat the process. I only work in the AM on a Sunday 🙂

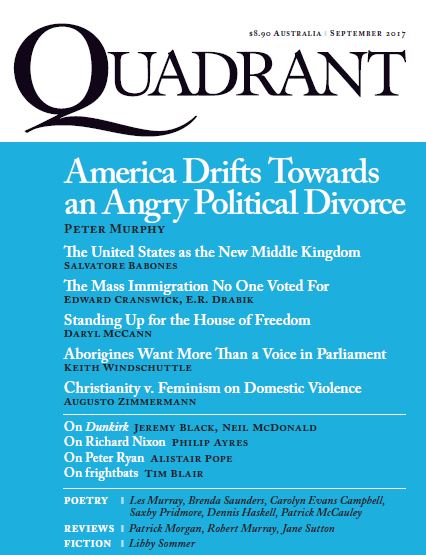

It took me 4 years to write The Crystal Ballroom. The chapters are self-contained, so I was able to send some of the discreet episodes out to Quadrant magazine for publication.

I belong to a weekly feedback writing group where we critique each others’ work. So I write to that weekly deadline. In the early years, when I’d finish a manuscript I’d pay an editor or mentor to read it and give me feedback. I’d also ask a couple of friends to read it and give feedback. I never send a manuscript to an agent or a publisher that hasn’t been reworked 20 to 100 times – that includes the rewriting along the way.

My Year With Sammy was my first published book. It was accepted straight away by Ginninderra Press, a small but prestigious publisher (thought-provoking books for inquiring readers). It was my fifth book length manuscript. I had sent the previous books to agents and large publishers. All my confidence had been knocked out of me by all the rejections leading up to the fifth manuscript. Now though, I have Ginninderra Press who seem to like my work. They also published The Crystal Ballroom this year. The Usual Story will be published by Ginninderra Press next year.

It’s an extremely difficult road to publication and some people decide to self-publish rather than continue to be rejected. But other people are able to write a best-seller, an airport book that sells lots of copies, so big publishers like their work very much. Unfortunately, or fortunately, my books are classified as literary fiction, so a very small market. Big publishers are not interested in books that do not conform to the norm. Not enough money in it for them.

I am very grateful to have my small but prestigious publisher.