This story was written just after The Sydney Olympic Games in 2000. A lot of Sydneysiders vacated Sydney during this time in anticipation of gridlocked roads, etc, leaving the rest of us to enjoy the Olympics along with all the tourists.

This story was written just after The Sydney Olympic Games in 2000. A lot of Sydneysiders vacated Sydney during this time in anticipation of gridlocked roads, etc, leaving the rest of us to enjoy the Olympics along with all the tourists.

He leaned back on the chrome chair, stretched his legs out under the square black table and placed his mobile phone in front of him. He looked over to the counter at the back of the cafe at the cakes and muffins on display and the Italian biscuits in jars. He turned back to the glass windows and wondered if he had the guts to tell her today. He wanted to. By Christ he wanted to. He straightened up, his elbows on the table, his hands clasped together in front of his face. There’d been some good times, that’s for sure. But what the heck. A man’s got to do what a man’s got to do.

The sliding glass door clanked open and Anny walked in. He looked over at her, first from the rear as she closed the door and then as she approached, her face flushed, her dark hair flying back from her shoulders. Not bad looking. A bit on the heavy side but not a bad looker all the same. Yes, there’d been some good times. Especially in the sack.

Every once in a while, when I’m scratching around for something new to write, I make a list of the things I obsess about. Thankfully, some of them change over time, but there are always new ones to fill the gap.

It’s true that writers write about what they think about most of the time. Things they can’t let go: things that plague them; stories they carry around in their heads waiting to be heard.

I used to get my creative writing groups to make a list of the topics they obsess about so they could see what occupied their thoughts during their waking hours. After you write them down, you can use them for spontaneous writing before crafting them into stories. They have much power. This is where the juice is for writing. They are probably driving your life, whether you realise it or not, so you may as well use them rather than waste your energy trying to push them away. And you can come back to them repeatedly.

One of the things I’m always obsessing about is relationships: relationships in families, relationships with friends, relationships with lovers. That’s what I tend to write about. I think to myself, Why not? Rather than repress my obsessions, I explore them, go with the flow. And life is always changing, so new material keeps presenting itself.

We are driven by our passions. Am I the only one who thinks this? For me these compulsions contain the life force energy. We can exploit that energy. The same with writing itself. I’m always thinking and worrying about my writing, even when I’m on holidays. I’m driven.

But not all compulsions are a bad thing. Get involved with your passions, read about them, talk to other people about them and then they will naturally become ‘grist for the mill’.

What about you? Do you find yourself writing about the same situations over and over again?

‘Around the World In Fifty Steps’ was my first published short story. It was 2001 and I’d just graduated with an MA in Professional Writing from the University of Technology Sydney. A heady time to see my name in a prestigious literary journal like Overland, progressive culture since 1954. I’d written the story originally as a synopsis for a book. Although the book never did find a publisher, I was very happy that the synopsis was published as a short story. Not bad for a high school dropout. Continue reading

When I used to teach classes to beginning writers, it was good. It forced me to think back to the beginning to when I first put pen to paper. The thing is, every time we sit down and face the blank page, it’s the same. Every time we start a new piece of writing, we doubt that we can do it again. A new journey with no map – like setting off towards the horizon alone in a boat and the only thing another person can do to help is to wave from the shore.

So when I used to teach a creative writing class, I had to tell them the story all over again and remember that this is the first time my students are hearing it. I had to start at the very beginning.

First up, there’s the pen on the page. You need this intimate relationship between the pen and the paper to get the flow of words happening. A fountain pen is best because the ink flows quickly. We think faster than we can write. It needs to be a “fat” pen to avoid RSI.

Consider, too, your notebook. It is important. The pen and paper are your basic tools, your equipment, and they need to be with you at all times. Choose a notebook that allows you plenty of space to write big and loose. A plain cheap thick spiral notepad is good.

After that comes the typing up on the computer and printing out a hard copy. It’s a right and left brain thing. You engage the right side of the brain, the creative side when you put pen to paper, then bring in the left side, the analytic side, when you edit the print out as you settle back comfortably with a drink (a cup of tea, even) and read what you’ve written.

Patrick White said that writing is really like shitting; and then, reading the letters of Pushkin a little later, he found Pushkin said exactly the same thing. Writing is something you have to get out of you.

Whether writing a story or writing a blog, start writing, no matter what.

Sounds, sights, and smells are all part of creating an atmosphere.

‘The creation of the physical world is as crucial to your story as action and dialogue. If your readers can be made to see the glove without fingers or the crumpled yellow tissue, the scene becomes vivid. Readers become present. Touch, sound, taste and smell make readers feel as if their own fingers are pressing the sticky windowsill.

‘If you don’t create evocative settings, your characters seem to have their conversations in vacuums or in some beige nowhere-in-particular. Some writers love description too much. They go on and on as if they were setting places at the table for an elaborate dinner that will begin later on. Beautiful language or detailed scenery does not generate momentum. Long descriptions can dissipate tension or seem self-indulgent. Don’t paint pictures. Paint action.’ – Jerome Stern, Making Shapely Fiction

Bringing in sensory detail is a way to enrich a story with texture to create the fullness of experience, to make the reader be there.

What about you? Do you use the senses, apart from sight, to create atmosphere?

Her Amber Necklace

my mothers dead

my mothers dead my brother said

he jumped in the air and

clicked his heels together

her children and grandchildren

and great grandchildren all came

jumping and bouncing

on forbidden chairs

we all laughed

now

distant lights scatter black night

a bus rumbles up Bondi Road

clock ticks in the empty kitchen

only the ticking

then

a dog barks outside

her woollen jumper warms me

her amber necklace hugs my neck

Copyright © Libby Sommer

First published ‘The Thirteenth Floor’ XIV UTS Writers Anthology

Header Image: Creative Commons

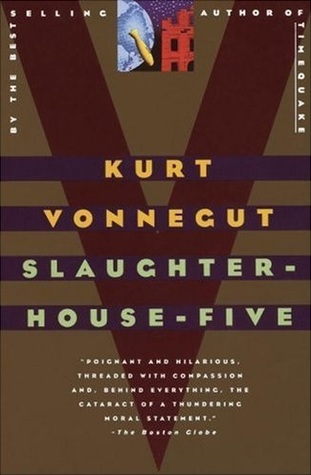

A fantastic example of this writing advice is Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five.

Poignant and hilarious, threaded with compassion and, behind everything, the cataract of a thundering moral statement. – The Boston Globe

Kurt Vonnegut’s absurdist classic Slaughterhouse-Five introduces us to Billy Pilgrim, a man who becomes unstuck in time after he is abducted by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore. In a plot-scrambling display of virtuosity, we follow Pilgrim simultaneously through all phases of his life, concentrating on his (and Vonnegut’s) shattering experience as an American prisoner of war who witnesses the firebombing of Dresden.

Don’t let the ease of reading fool you – Vonnegut’s isn’t a conventional, or simple, novel. He writes, “There are almost no characters in this story, and almost no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick, and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces. One of the main effects of war, after all, is that people are discouraged from being characters.”

Slaughterhouse-Five is not only Vonnegut’s most powerful book, it is also as important as any written since 1945. Like Catch- 22, it fashions the author’s experiences in the Second World War into an eloquent and deeply funny plea against butchery in the service of authority. Slaughterhouse-Five boasts the same imagination, humanity, and gleeful appreciation of the absurd found in Vonnegut’s other works, but the book’s basis in rock-hard, tragic fact gives it a unique poignancy – and humor. – Goodreads

Highly recommended. A masterpiece.

This was in a far distant land. There were Pilates classes but no surfing beaches or vegan restaurants. People said to hell with low-fat diets and tiny portions. Charles, who had wanted her to hire his friend Jean-Pierre as tour guide, had encouraged her in yoga class. ‘Look, Zina, you’re a facilitator—you’ve been running those groups—for what—thirty years?’

‘Only twenty, for goodness sake.’ She had turned forty-nine and frowned at him upside down between the legs of a downward facing dog. She had a face marked by the sun, a face left to wrinkle and form crevasses by years of smoking, a face made shiny by the application of six drops of jojoba oil, although the shop girl had recommended she use only three. ‘I love that word facilitator. It says so much.’

‘Twenty. All right. This guy’s not at all your type. He’s a numbers man. He shows tourists around in between Engineering contracts. He can show you how to buy a bus or a train ticket, how to withdraw money out of the wall—get your bearings. You can hire him for half a day. Or, in your case, half a day and half the night.’

‘Very funny,’ she said, stifling a laugh. Now they were on all fours arching their backs like cats, then flattening their spines to warm up the discs. Indian chanting music took your mind off the fact that the person behind you was confronted with your broad derriere. ‘So what’s the story with Jean-Pierre?’ Continue reading

The Inciting Incident is the event or decision that begins a story’s problem.